Betty ‘Duffy’ Ayers, artist, born 19 September 1915; died 10 November 2017.

Duffy was born Betty FitzGerald, with an identical twin, Peggy, in Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire. Their father, William FitzGerald, the feckless brother of the Irish nationalist politician and poet Desmond FitzGerald, abandoned the family when the twins were very young. Their American mother, Laura (nee Farlow), felt she had no alternative but to leave her daughters in a convent school on the Kent coast while she went to teach English in Turkey.

While the other pupils went home for their holidays, the FitzGerald girls stayed with the nuns, who treated them, they recalled, with great cruelty and starved them of affection. The girls did not recognise their mother on her return after seven years’ absence. Emotionally, Duffy was deeply scarred by this long childhood experience but it consolidated in her a remarkable stoicism and strength of character, and she was herself the gentlest of women.

Peggy and Duffy.

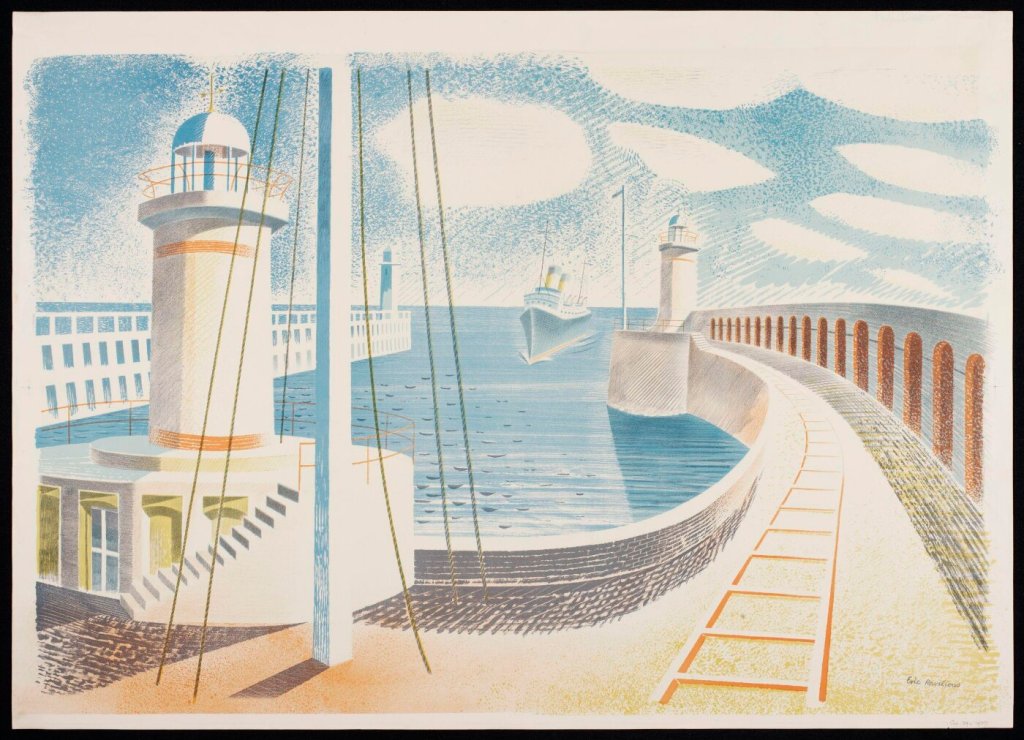

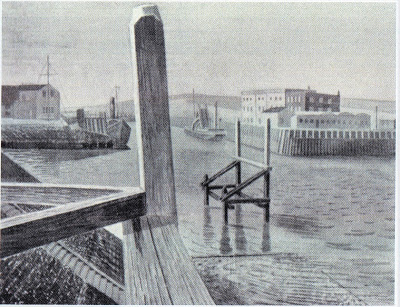

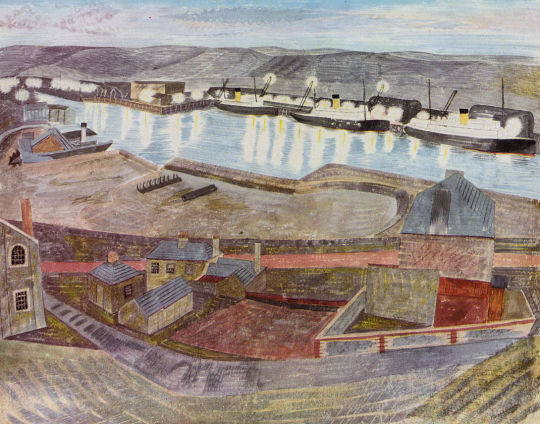

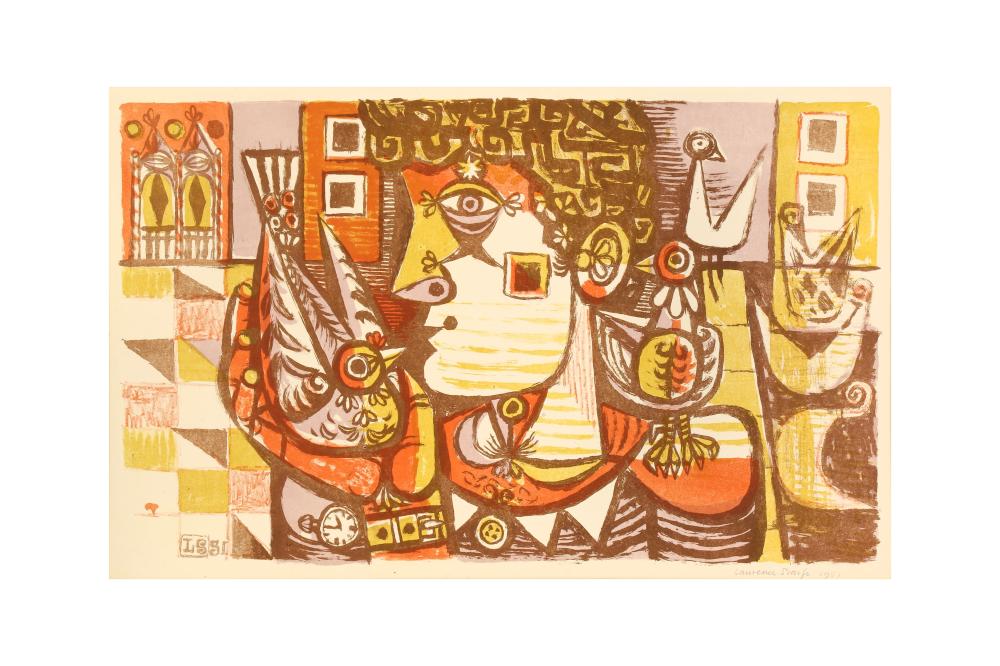

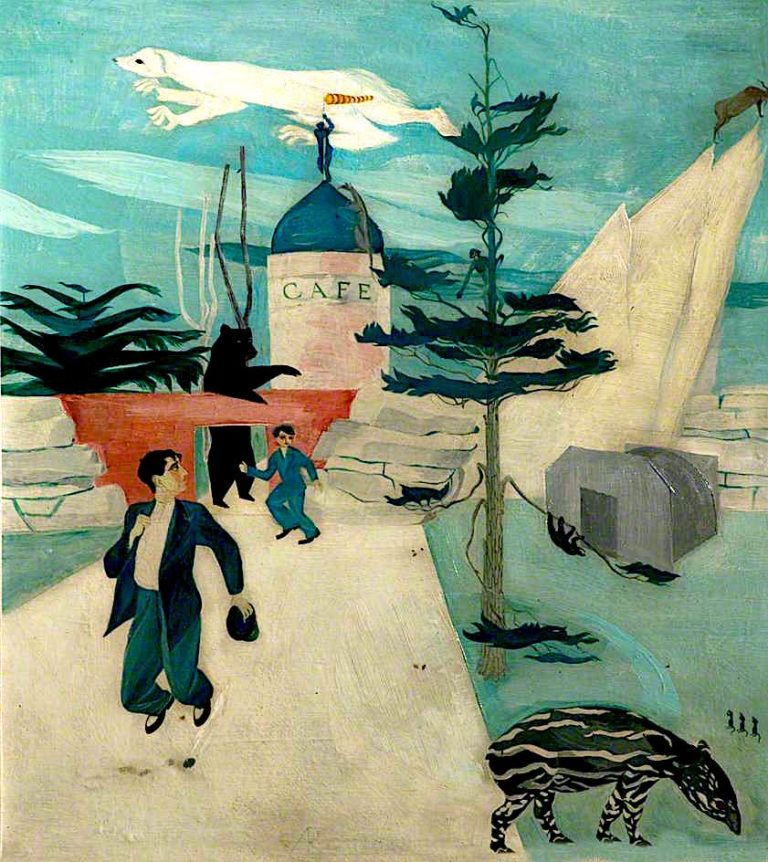

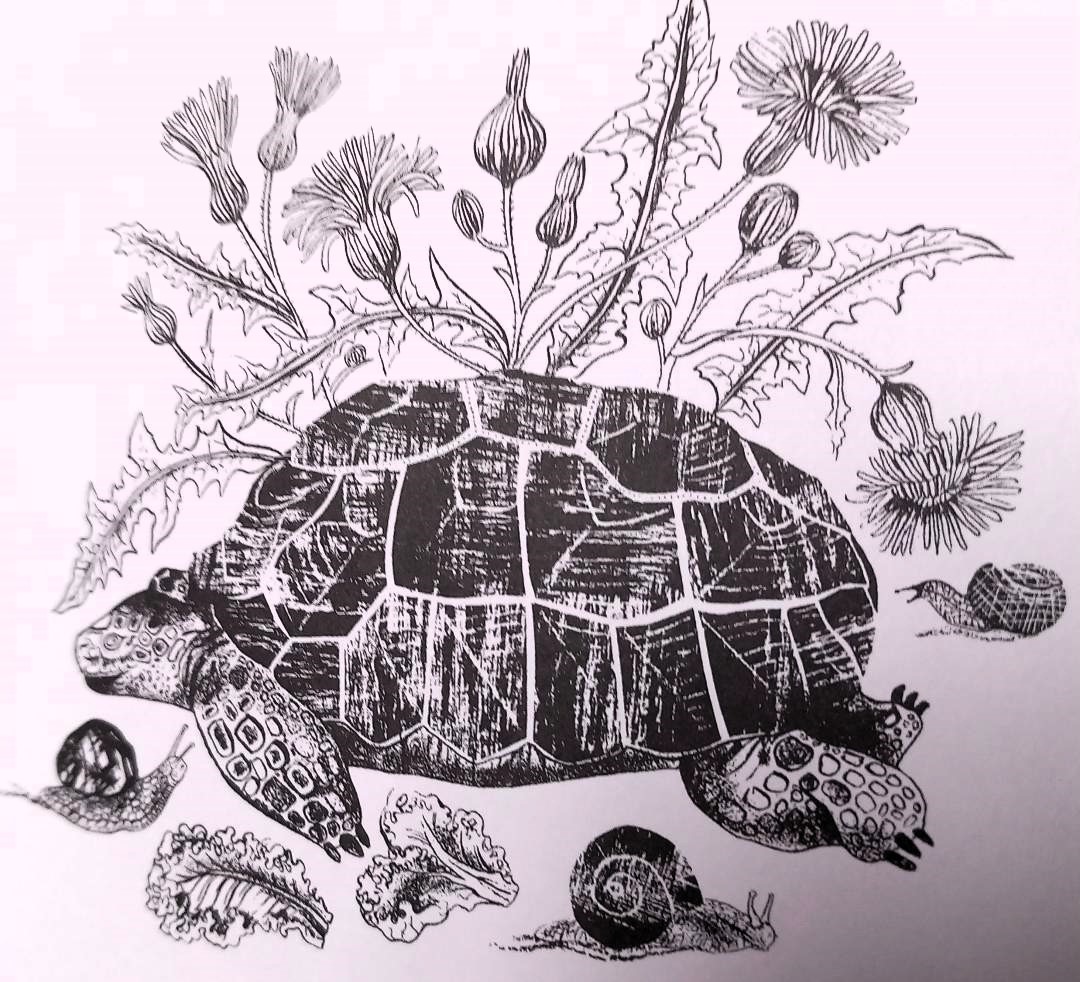

In the early 30s Duffy attended the Central School of Art in London where she met Michael Rothenstein, later to become one of the leading printmaker-artists of his generation. They married in 1936, she 21, and moved to Great Bardfield in 1941. They lived initially in Chapel House (in the grounds of John Aldridge’s Place House) before moving to Ethel House in the High Street.. The north Essex village was home to a distinguished community of artists from the 1930s to the 60s, including Eric Ravilious, Edward Bawden, Tirzah Garwood and John Aldridge.

Duffy’s emergence from the extreme unhappiness of her schooldays no doubt deepened her empathy, during their first years together, with Michael’s slow recovery from the melancholia of myxoedema (arising from a thyroid condition) that had afflicted him throughout his 20s.

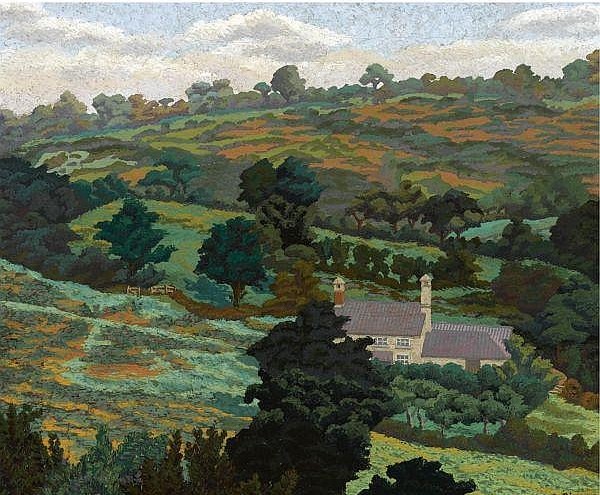

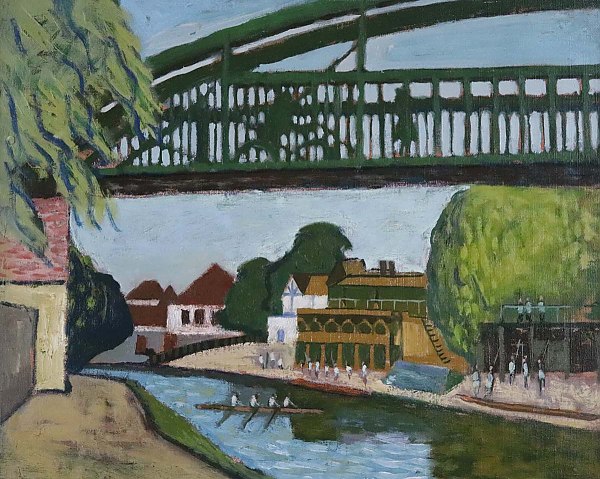

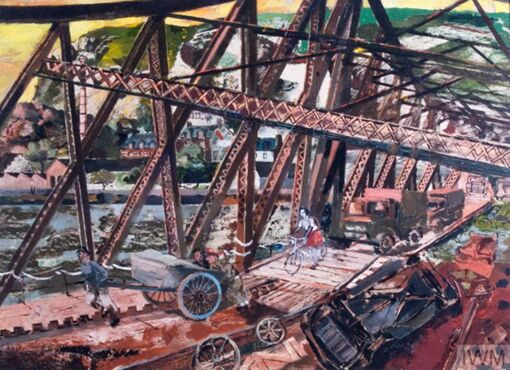

Kenneth Rowntree’s painting of Ethel House.

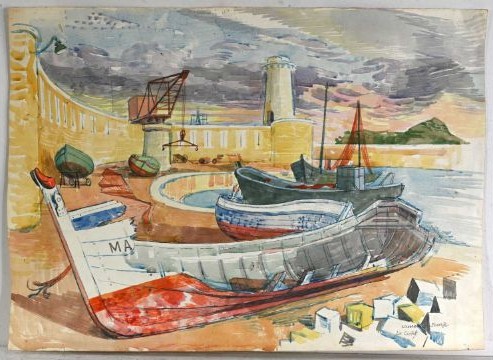

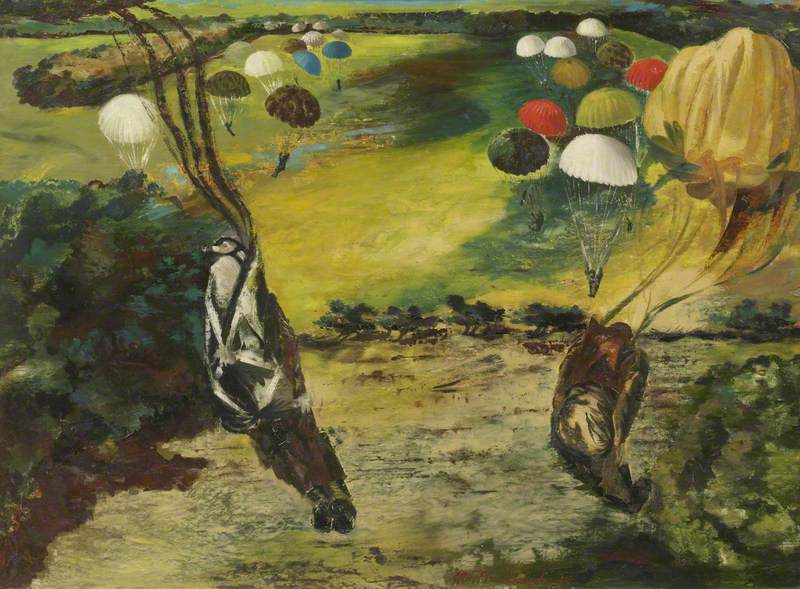

Duffy did little of her own work during these years, but she collaborated with Michael on large-scale paintings and later assisted his printmaking. During the second world war she made few paintings of her own but worked at times with the designer Peggy Angus on wallpaper designs.

Duffy was a gifted portrait painter and an early subject was Tirzah Garwood wife of Ravilious lost over Iceland in 1942.

Later she taught art to the local women of the Women’s Institute proving to be a gifted teacher who encouraged original work of remarkable quality. During the war she maintained a lively correspondence with Robert Graves, a pre-war friend who was a regular visitor to Great Bardfield now living back at home in Deya, Majorca following an exile during the Spanish Civil War and WW2.

During the war Duffy was almost killed when a bomb fell near a bus she was on. “I escaped because I was on the top floor,” she said.

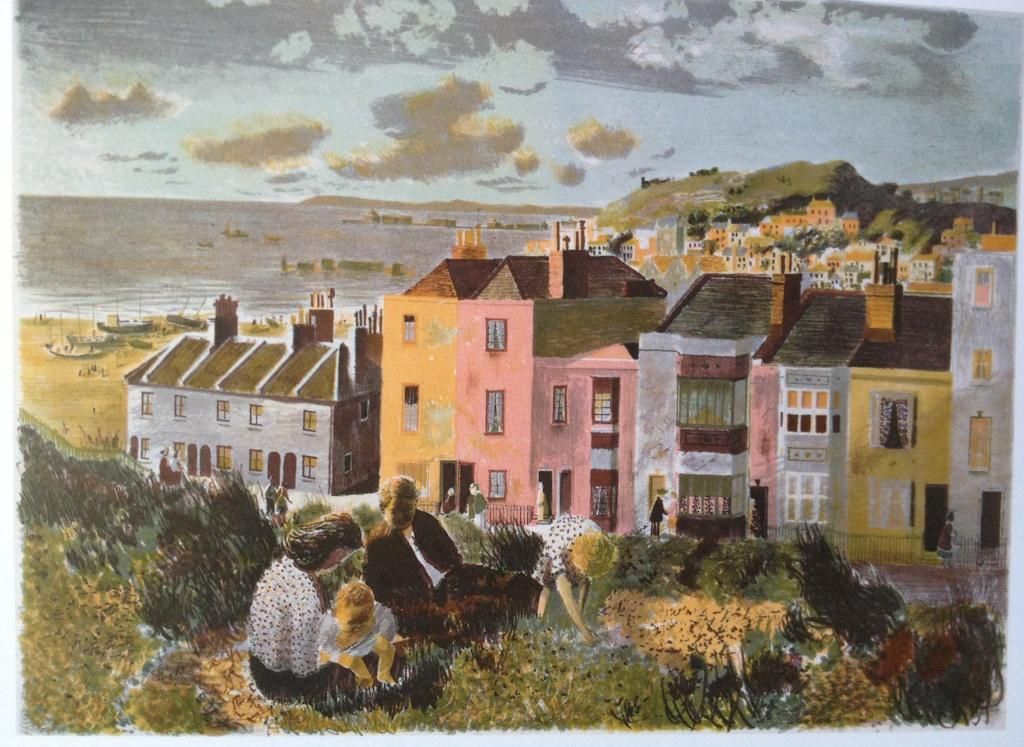

Portrait of Kitty Wilson 1945. Fry Art Gallery. Kitty Wilson was a remarkable woman. Born in Deal, she worked for Dr Barnado’s in Essex for several years, caring for young disabled girls. In 1929 she travelled to Kalimpong in India to look after deprived children, returning to Essex after three years due to health problems.

Duffy and Michael’s son Julian, later founder of Redstone Press, was born in 1948, and daughter, Anne, who became an artist, was born in 1949.

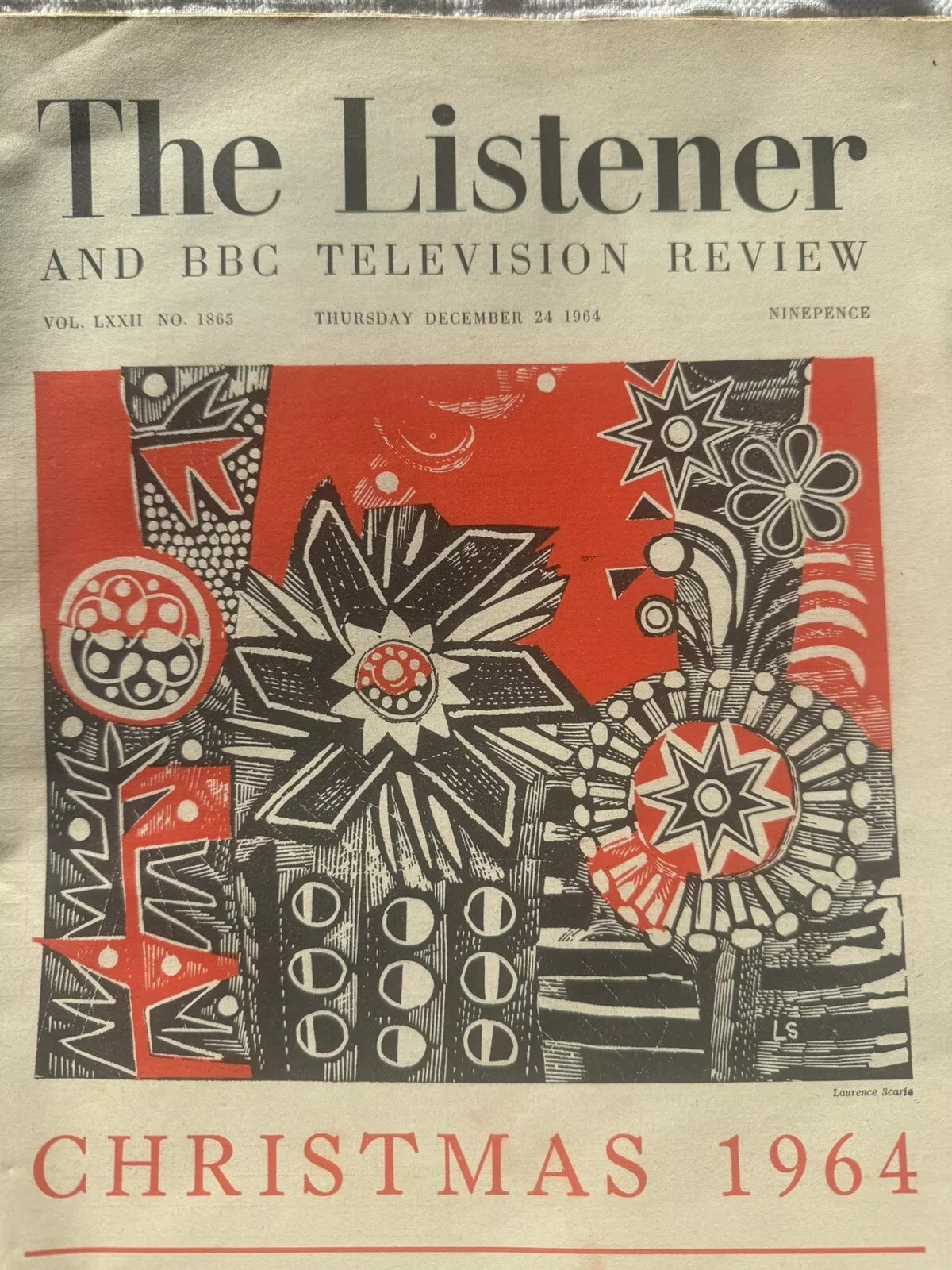

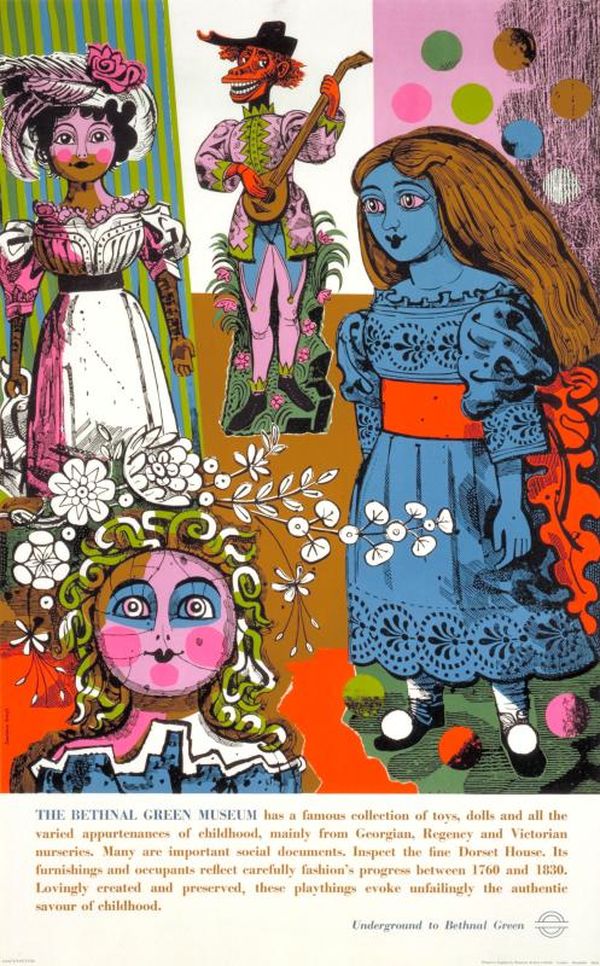

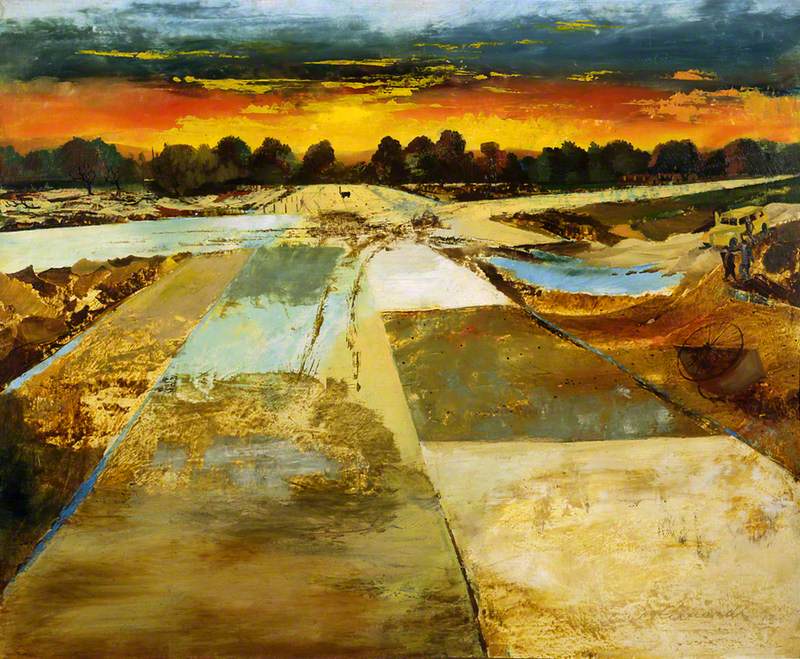

By the mid-50s, Great Bardfield had become famous for its popular Open House exhibitions, initiated in 1951, when several of its artists were employed on murals and design work for the Festival of Britain. For several years, for a summer fortnight, thousands of art lovers descended on the village to traipse through the artists’ houses, delighted by a figurative English modernism that was accessible and stylish, often depicting the life of the village and the landscape around it. During the 40s and early 50s Duffy was a lively presence at the heart of this social and artistic activity. Michael had by this time set up printmaking facilities at Ethel House on the High Street (later enlarged with a studio extension by Frederick Gibberd).

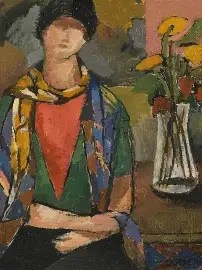

Left: This painting has a strange history. Duffy painted herself, or her twin sister, in the 1950s (she was then Duffy Rothenstein). But she threw the painting away (perhaps she was dissatisfied with it) and it was literally rescued from the wastepaper basket by the babysitter, Mrs Perkins. Her son Don Perkins gave it to the Great Bardfield Historical Society in 2011. Right: Self Portrait by Peggy Fitzgerald, Tullie House Gallery, Carlisle.

In 1955 Duffy and Michael separated, and they divorced in 1956. Duffy married the graphic artist, Eric Ayers (1921-2001). “He was always waiting in the wings,” she said. Duffy left Great Bardfield, and stopped painting for many years. Following her second marriage, to Eric Ayers, she moved to a Georgian house in Bloomsbury, central London, where she lived for the rest of her life. She showed regularly at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibitions, and in commercial galleries.

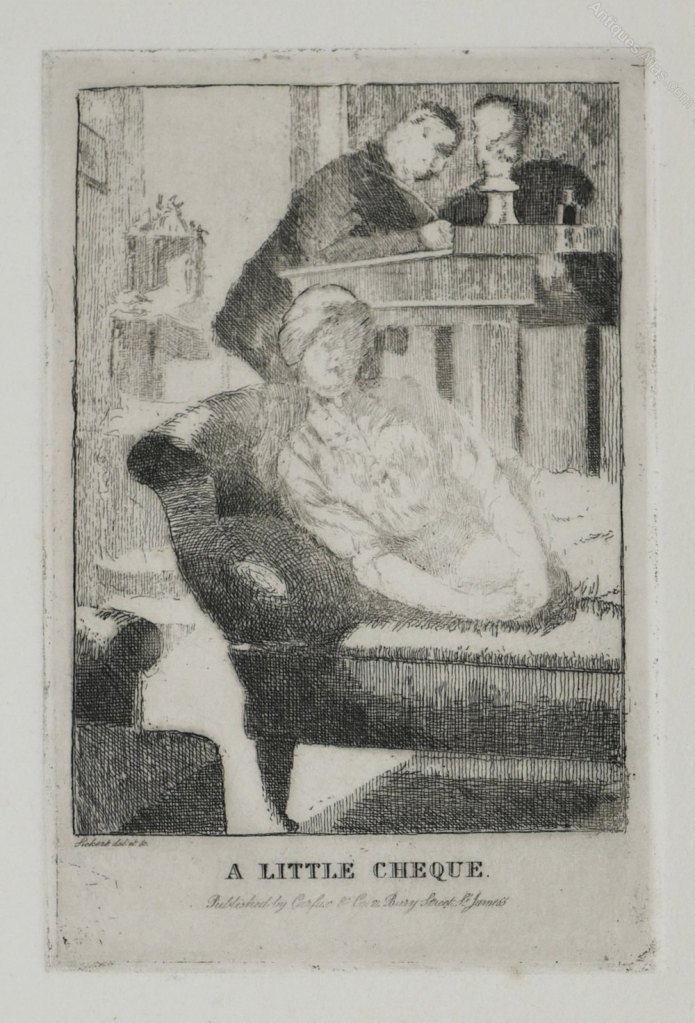

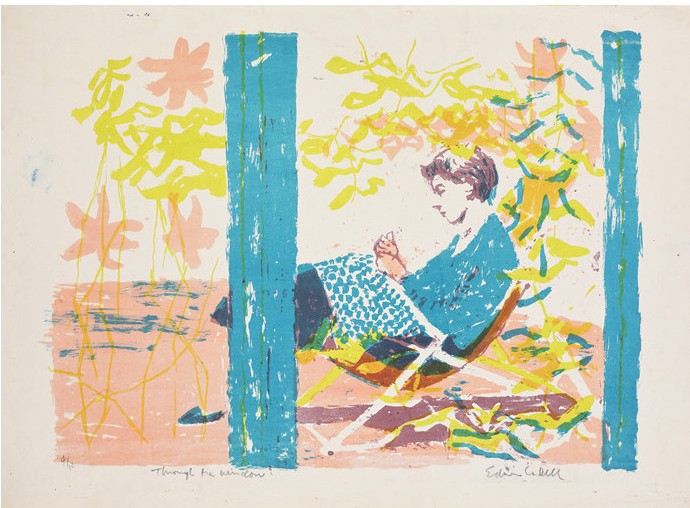

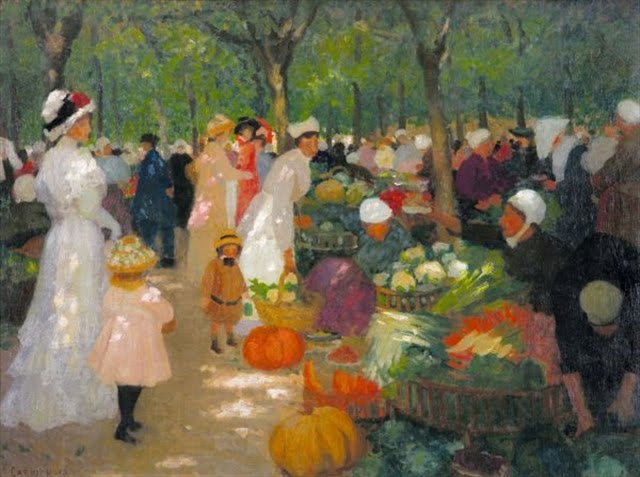

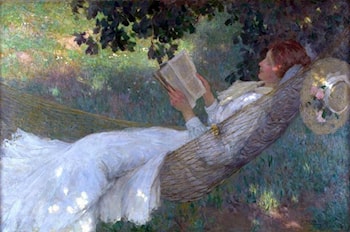

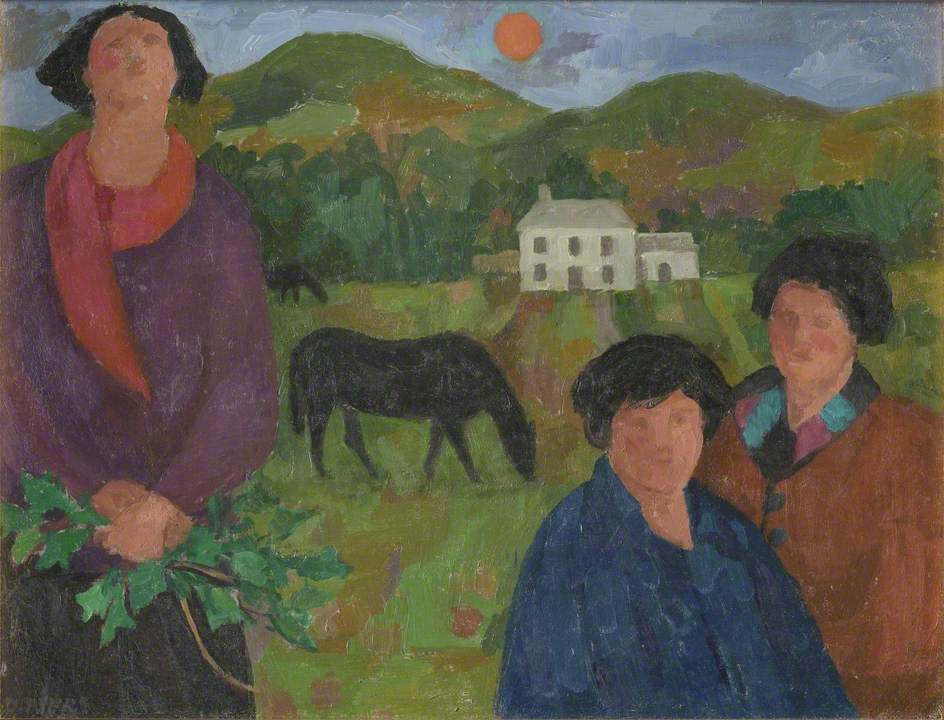

Still Life Reclining Nude The Hill Farm Girls

Duffy’s work included a few still life paintings but mainly women, full face in ageless garments. She avoided landscapes, “leaves are horrid repetitious shapes !”

Top left: Scarves, date unknown, Fry Art Gallery. Middle: woman with Scarf. Top right: Unknown. Bottom left: Olive in her garden, presume friend Olive Cook. women in White, 1996. Right: Family Group.

Top left: Girls with Dog. Middle: Girl with Fishes. Tope right: The Apple Eaters. Bottom left: Girls in Blue (portrait of Anne), Fry Art Gallery. Bottom right: Ink Drawing of Daughter Anne.

After Eric died in 2001, Duffy carried on painting until a fall left her frail. In 2006 an Australian couple, Sven Klinge and Belinda Murphy, moved in as temporary carers; they stayed for 11 years. They kept Duffy alive and alert, steered her through many interviews about her years in Great Bardfield and monitored her increasing dementia. Despite the late onset of blindness, her final decade may well have been one of her happiest. Duffy died in November 2017 at the age of 102

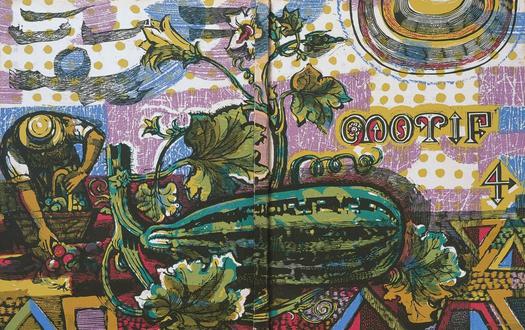

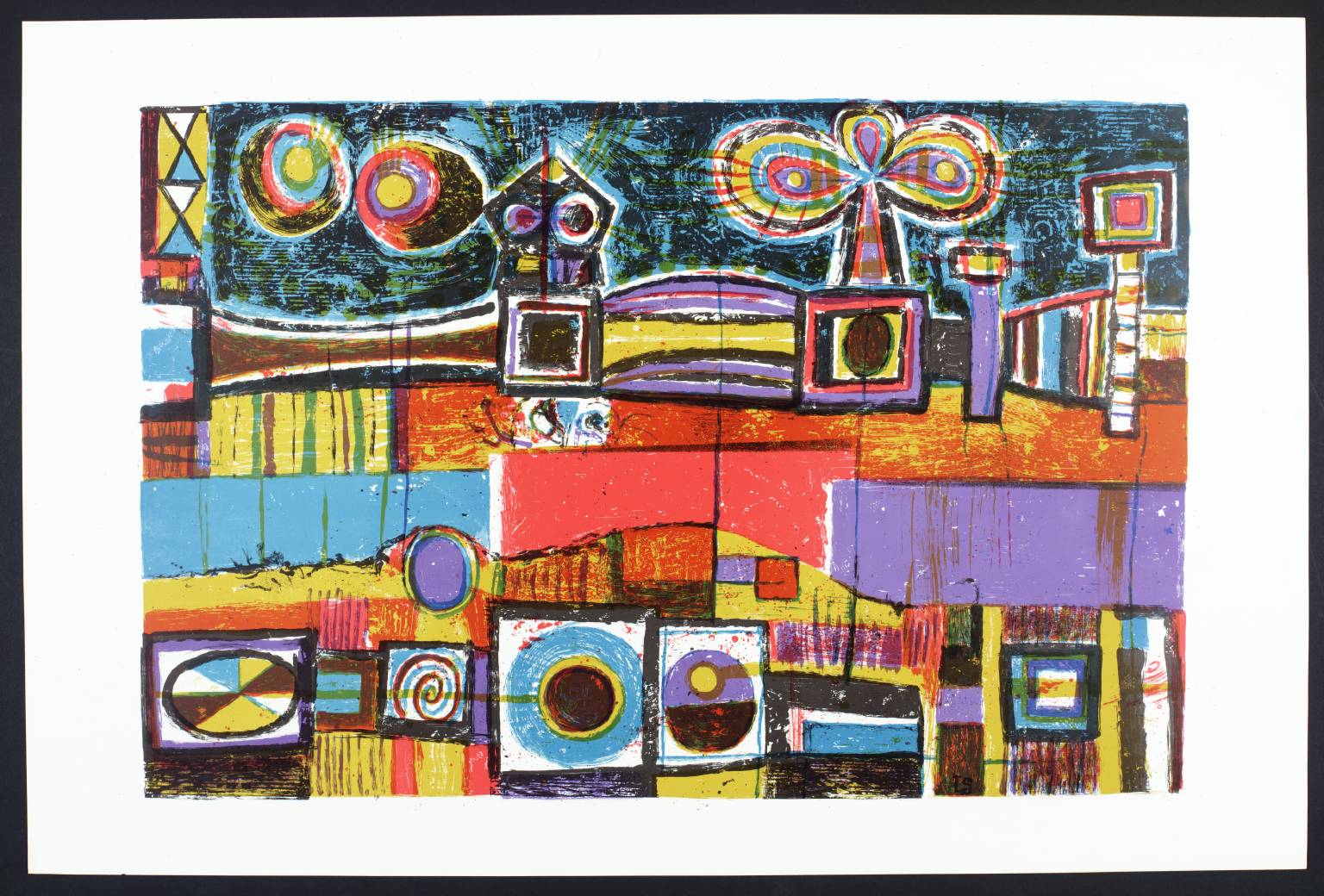

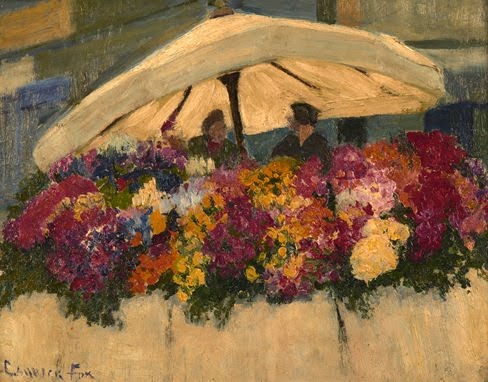

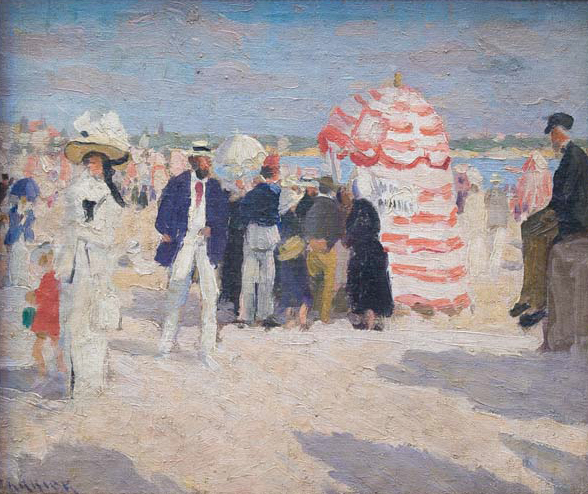

Under the Sun, 1999.

Duffy attributed her long life to simple living. “I used to smoke but I stopped years ago, and for a long time now I have lived an austere life, never eating too much or drinking – though I still like the odd glass of red wine.”

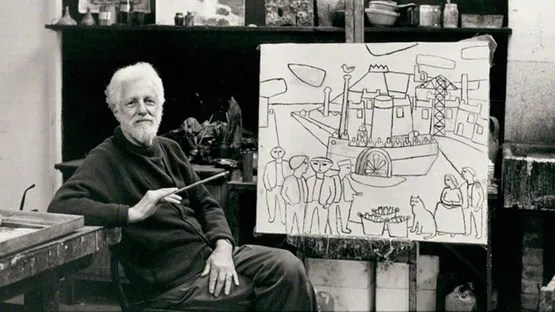

Duffy at home, 4 Regent Square, by Richard Bawden 2009.

Graham Bennison, November 2025, Thanks to Wikipedia but mostly to Mel Gooding, Guardian 11th Dec. 2017 who penned Duffy’s obituary which forms most of the text here given the lack of other sources.